Let Go The Urn

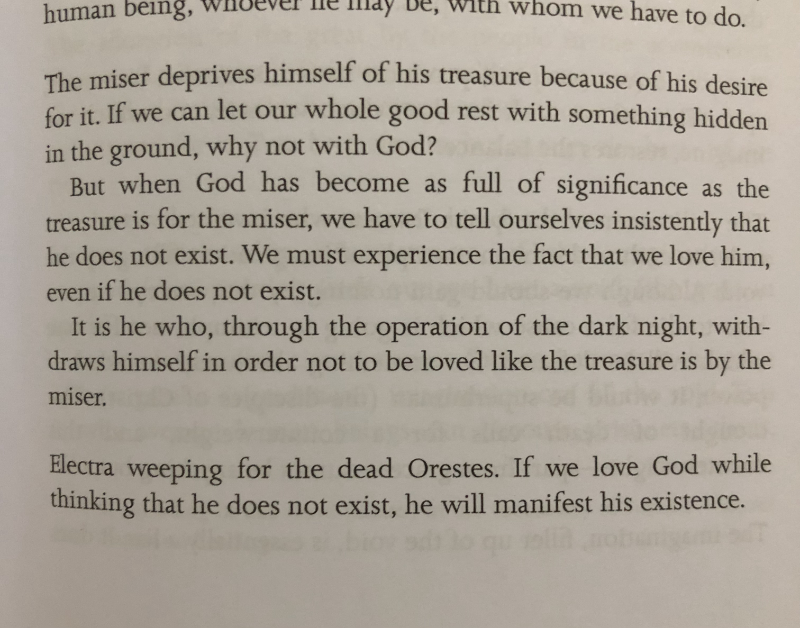

This is an excerpt from Simone Weil’s essay on detachment from Gravity and Grace. When I first read those last two sentences I was unfamiliar with the reference and confused as to what she meant. I put the book down and decided to move on to another book of hers, Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks. It was here in the second chapter that I found her full exploration of the Sophocles play, Electra and it struck a chord deep within that got me to thinking.

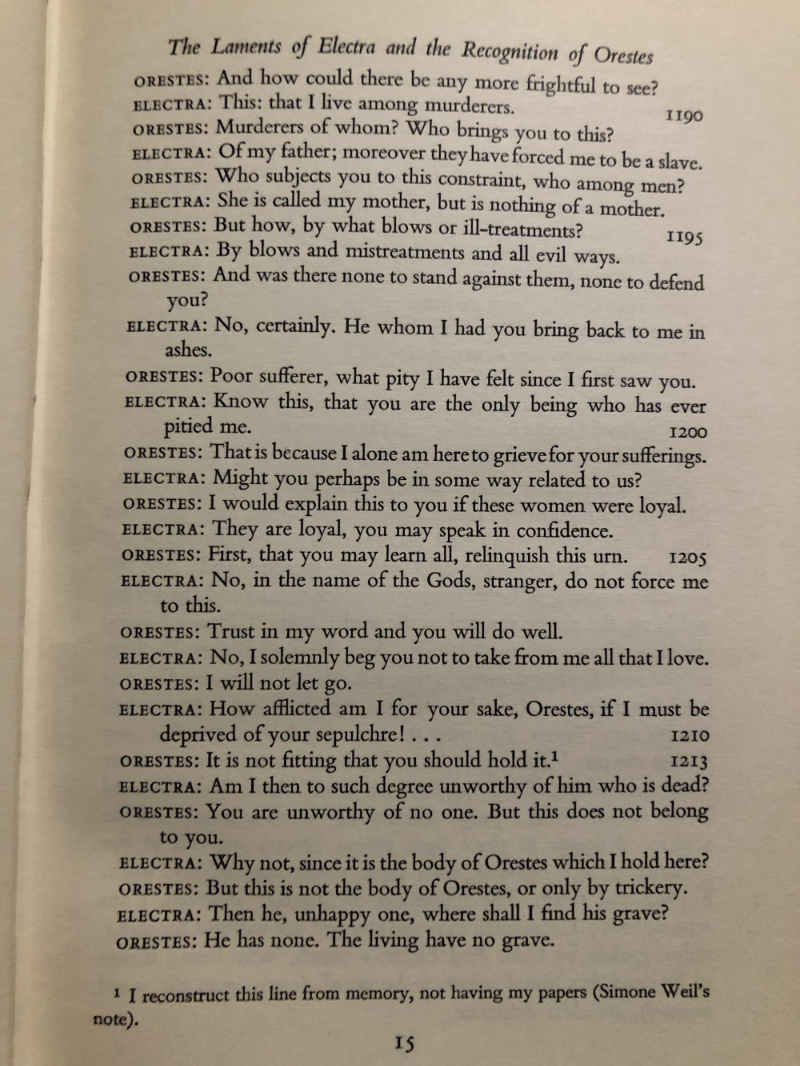

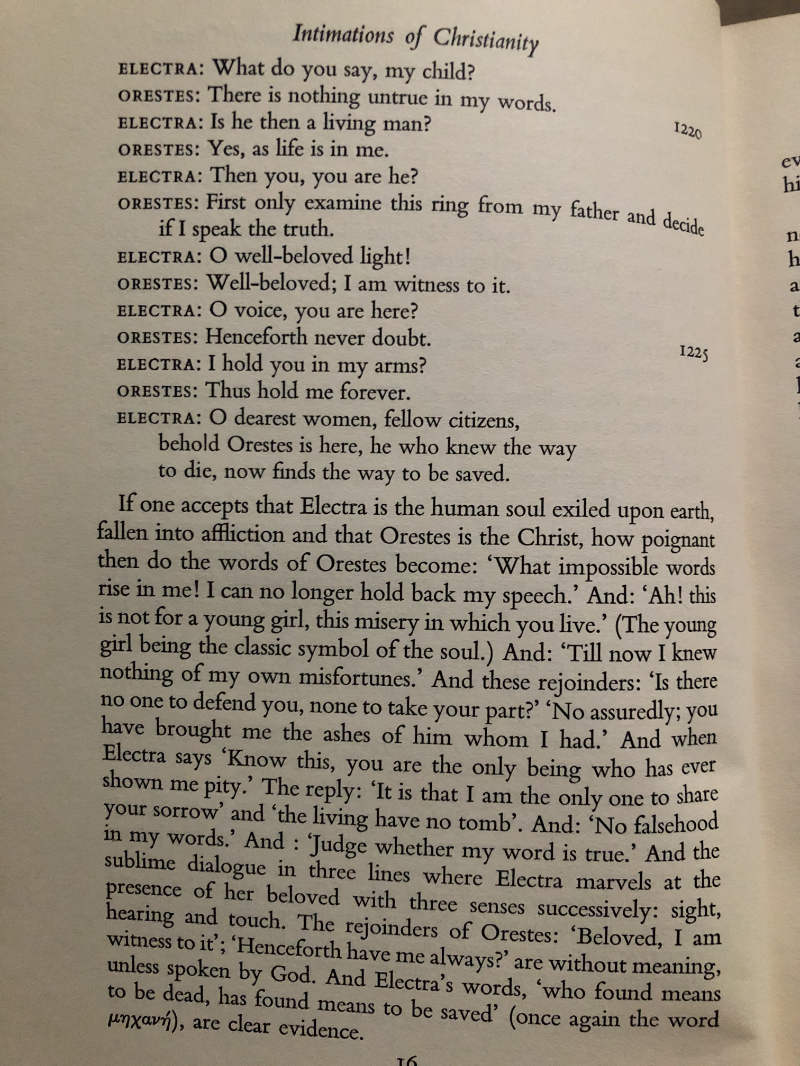

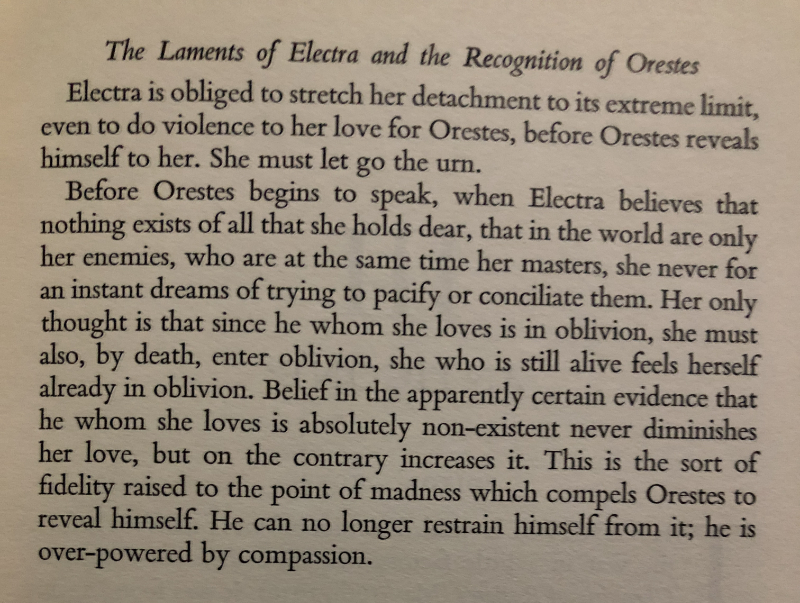

Electra was separated from her young brother Orestes for many years. In that time she had been reduced to a common slave by her mother, who had killed her father, and Electra was beset on every side by those of the house who tormented her at every opportunity. One day a young man comes to her bearing an urn with the ashes of her brother. She begins to lament the death of the only person left who loved her, and as she speaks the young man understands who she is. Here is their conversation and Weil’s commentary.

After reading this I now had a fuller understanding of what Weil was getting at.

In order for the human mind to properly understand something and communicate to others about it we must mentally attach to it a label, a small piece of arbitrary information that signifies it as belonging to a certain set of other things that have similar characteristics. In short, we must give it a name. This is an unavoidable necessity in order for human civilization to progress with any efficiency at all. We must order our world this way because we cannot come up with a unique name for every separate object we encounter.

Thus we progress by category through our education in the world we inhabit. Our young brains, the pattern seekers that they are, soon want to know all about every category that there is, and our newly acquired motor skills raise our small finger and we ask “What’s that?” over and over until the adults despair that we will ever stop. And hopefully, if we are reared in a supportive environment, we will never stop but progress from tree, book and chair, to less tangible things like A, B and C and onward still to understand things like justice, mortality and mercy.

Through this process we gain a sort of mastery over our world. We begin to define ourselves by certain ideas and beliefs. We start to become sure of our concepts and begin to make assumptions and speculations about how the world will progress going forward. Sometimes those assumptions are challenged by reality, which forces us to reevaluate our understanding and shakes our faith in ourselves. Only rarely is this type of revelation a happy one. More often than not it is our own private apocalypse so we do our best to insulate ourselves from such epiphanies and build inner and outer lives of comfortable predictably. And in this we suffer ourselves the allusion that the world bends, more often then not, to our will.

This is also a necessity, a convenience that hopefully has some tether to reality. A necessity that allows us to progress through our day without constantly reevaluating the universe and our place in it. This structured reality is a type of ownership. We make predictions about our world and the people in it and when everything obliges us by seemingly obeying our will we feel that all is as it should be.

These mechanisms apply to every aspect of our lives with mostly benign results but we run unknowingly into trouble when we attempt to apply them to God. I say unknowingly because this mechanism of assumptions we have built barely supports the weight of our day-to-day reality that we can see, touch and feel. It fails completely when we try to apply it to a high and holy God. It is in Him that we meet a reality that we have no hope to ever comprehend, let alone categorize, predict and control. Yet we blissfully attempt to do so at every opportunity because it never occurs to us to do otherwise.

We think we know God but forget that this is only because He chose to reveal Himself to us. Because of this revelation and incarnation, we love Him but we must not fool ourselves into thinking that we fully understand Him, that we can speak for Him with absolute certainty. It is when we feel a strong need for certainty, an urgency to be right, correct in thought and action, that we must exercise the most caution lest we replace our desire for who we would like God to be ahead of who He actually is.

As powerful as our God-given gift of reason is, we must come to accept its limits as we approach the high and the holy. Our drive to be right, correct and certain can lead us away from justice and mercy when we convince ourselves that we have linked together enough scripture verses to know the mind of God and that He, conveniently, agrees with us. This is where our ideas about God can get in the way of our truly knowing God as more than just an creation of our own mind. When we cling to our assumptions about what we want to be right we are like the miser who cannot enjoy his wealth because of his possessions of it. The only action we can reliably take is to love God even when we do not have any presuppositions about who He is because we are completely incapable of bringing that level of understanding to the relationship. We have no language or words to truly convey the actual existence, the essence, of God. When we stop pretending that we know what we cannot know, that we understand what we cannot comprehend, when we stand there weeping over the fact that our language has failed us and that we, like Electra, have been clinging to an empty urn of our own design, then He is moved to manifest His existence as the one who has been searching for us all along.

This is the logos, the Word, the understanding that Christ brings to us. The thing that we must know that we cannot know. It is the knowledge of the active, pursuing love of God. This was a love that could not be told to us in the signs and symbols of langage. It could only be expressed in the physical existence of the God Himself. Something tangible that we can point to and ask "what's that?" and thus come to know the extent to which we are loved. I don’t think it is a coincidence that the same apostle who made the connection to Platonic revelation also told us the God is Love, full stop.